Phase 4: Site Selection and Design

This phase covers information Native developers may need to know about taking your housing project from a vision on paper to a brick-and-mortar, livable apartment home. Understanding site environmental factors, obtaining approvals and using building codes for the design, and making last-minute cost tradeoff decisions are all important roles for your organization to undertake.

The most successful development projects involve a high-level of collaboration between different partners such as TDHEs, TDHAs, architects and engineers, community members, tribal leaders, funding agencies, and contractors. An integrative design process will ensure that collective long-term goals and vision are included throughout the design and approvals phase of development. It also allows projects to maintain the uniqueness of place and culture that is important in housing development, especially on Native lands. [58]

By the end of this section, developers will understand the unique and necessary steps to designing and approving new development on Native land.

-

Site Selection and Approval to Build

-

Site Suitability: General Factors

-

Site Selection

-

Site Alignment with Financial Resources

-

Gaining site control

-

Design

-

Developing the Site Plan

-

Obtaining Approvals

-

Building Codes on Trust Lands

-

Climate Resilience and Sustainable Development

Site Selection and Approval to Build

To find buildable land for your development project, you will need to evaluate different parcels of land to determine which site(s) best meet your project goals. This evaluation process is often referred to as “site selection.” Site selection influences practical aspects of your development project, including the overall financial feasibility, design, and ability to align with community needs. This section outlines three factors that are especially important to explore for projects on tribal lands.

Site suitability: General factors

Site suitability examines site characteristics such as slope, soil, and parcel size and shape, to understand if the site’s existing physical conditions require significant work to prepare a site for development. If significant site work is needed, it will result in additional project costs. It is important to work with your EPA or Environmental department including Planning as they can help with a lot of the natural or environmental systems, including information from flood-plains or wetland areas to 100 year old walnut trees. If you are considering multiple sites for your development, you may want to consider those that need less site work prior to construction and can meet other social and economic development factors (discussed in more detail below) to help lower total development costs.

Physical factors

-

Slope is the change in elevation on a site. In general, steeper slopes translate into additional time and effort to prepare the site for development (moving soil, building retaining structures, and adding infrastructure). Most site selection guidance recommends avoiding sites with slopes with a grade of 10 percent or higher, given the amount of earthwork needed to improve the site.

-

Soil influences a range of factors for your development: ability to support overall development; ability to provide drainage; presence of sensitive ecological factors, such as wetlands. Soil surveys, like those available from the USDA or EPA, provide general soil conditions. In most cases, you will need to conduct onsite sampling and surveying to understand if a site’s soil can support your proposed development.

-

Parcel size and shape influence how your development will look once built, including how it connects to its surroundings and how buildings will be configured on it. For homes on tribal lands, parcel size and shape may affect your ability to achieve culturally relevant designs, such as being able to orient homes to a specific direction or cluster homes together due to tribal preferences to live in close proximity, or for practical purposes, such as reducing infrastructure costs.

-

Natural or environmental systems on the site informs how your proposed development will interact with the natural world, as well as any negative impacts that your development could create to these systems. While housing development tends to focus on environmental impacts defined by regulatory statutes, indigenous knowledge among tribal members may provide another lens to view the natural environment onsite and surrounding it. You will need to account for both perspectives – regulatory environment impacts and tribal members’ knowledge of environmental impacts – as you undertake your development project. For instance, the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe asks developers about the presence and potential removal of plants and vegetation, including ones used for medicinal purposes, and birds and animals observed on the site, as part of its environment assessment.

-

Environmental hazards or risks on the site will help you understand if your development will be located near environmental hazards, such as nonpoint source water pollution; ambient air pollution; or contamination, or if it will cause any of these hazards. Additionally, this assessment could extend to examine the impacts of climate change, such as sea level rise and extreme weather events, which poses a threat to many tribes. Many tribes are completing climate change vulnerability assessments to identify climate-related risks, which could serve to understand these risks surrounding your site in more detail.

Reference resource:

Social & economic connections based on site location

In addition to evaluating the physical characteristics of your site, you should also account for your site’s surroundings from social and economic perspectives. The most straightforward way to understand these surroundings may be to examine access to key series and destinations, such as public transit service, nearby healthcare facilities or schools, or existing gathering places. What connections matter will vary based on your development model and the vision and support of tribal leaders and members.

For development serving tribal members, it will be important for you to understand any social ties they want to maintain or enhance through this development, such as the incorporation of social features like shaded areas for each home or communal gathering spaces. In other words, how you build your project can also support these connections, even if they don’t exist today.

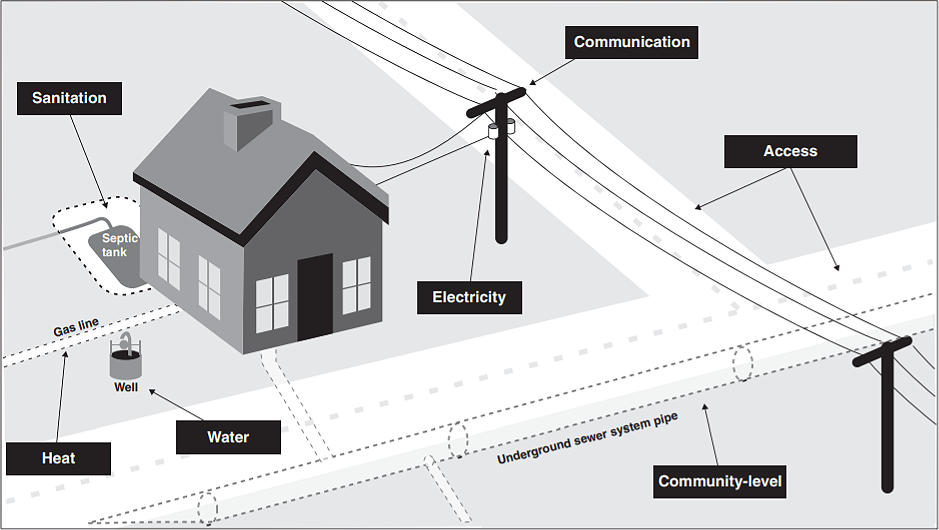

Common infrastructure needs on tribal lands

In a 2010 survey, NAHASDA grantees ranked lack of funding for housing-related infrastructure as the greatest problem with the NAHASDA program.

While the need for infrastructure on tribal lands exceeds the resources available, resources to fund infrastructure as part of your project exist through various federal agencies. NAHASDA, USDA, the Bureau of Indian Affairs all operate programs that support housing-related and other infrastructure improvements, although where it is available for your specific project may vary based on your housing model and specific tribe being served.[59] Tribes also have access to their own revenues, such as money from casinos or other enterprises, which could be another, flexible source for infrastructure improvements. The Department of Energy maintains a database of ongoing funding opportunities for tribes that span housing, economic development, and infrastructure programs, among others.

Defining infrastructure

In recent years, infrastructure has taken a broad definition to encompass housing, healthcare, childcare and education. This part of the guide focus on the physical infrastructure needed to support your development.

-

Sanitation (water & sewer) – Access to clean drinking water and adequate sewer systems is a persistent need for people living on tribal lands. On some sites, your project may require adding the appropriate infrastructure to your site and extending existing sanitation systems to your site to connect to the existing system. The costs associated with these improvements and connections can be costly, especially in more rural areas where these connections can span a large area. Additionally, cross-jurisdictional & cross-agency decision making; fractured land ownership; and lack of authority to acquire rights of way can also create challenges to extend or connect with existing sanitation systems.

Related funding sources: -

Indian Health Service Sanitation Facilities Construction Program

-

Energy – Development projects typically link up to existing utilities, including power grids. Some tribal lands are connected to a reliable energy source, while 14 percent of existing homes on tribal lands lack basic electricity entirely or use inefficient and costly types of electricity.[60] As a result, your site may need to extend infrastructure to the closest energy source (such as having a transformer installed). Like other types of infrastructure, the cost to add or connect to existing energy sources and lack of authority to acquire rights of way can pose challenges. You can consider onsite renewable energy sources and explore ways to use Native design and materials for your homes to minimize energy needs (like the approach used by the Pinoleville Pomo Nation, among others featured in this guide).

Related funding source: -

Telecommunications – Access to reliable telecommunication services, including broadband access, continues to be a challenge for many tribes. People on tribal lands are 4.5 times less likely to access broadband than those living elsewhere, and there are limited speeds and services available among homes with service.[61] Extending broadband to rural areas, in particular, poses a challenge because of the high cost of extending and providing ongoing service in remote or rugged areas. Your project can explore ways to incorporate telecommunications to your site by seeking funding to support broadband connectivity to your project, as well as explore integration of distributed access points on your site.

Related funding sources: -

Department of Commerce’s Connecting Minority Communities Program

-

Transportation – Roads on tribal lands may be owned and maintained by the BIA (one study estimated BIA maintains about 29,000 miles of roadways), while others are owned and maintained by tribes. If your site lacks access to the existing road network, you may need to extend it or upgrade it if your project will result in additional traffic. You should work with tribal leaders who administer transportation funding to identify ways to coordinate with their available resources, which could help offset your costs, or opportunities to add transit service to your site.

Related funding sources:

Site selection: Key factors on tribal lands

This section examines three key factors on tribal lands:

-

Cultural or Historical site significance

-

Infrastructure Capacity and Needs

-

Land use Context and Zoning

Factor #1. Cultural or historical site significance

Tribal lands are places of rich cultural, spiritual, and historic significance, and you will need to understand this significance as you assess potential sites for your development. In terms of historic significance, you should investigate if your site is on or located near any known or suspected historical sites; known for traditional uses; or if buildings on it are considered historic or cultural landmarks. In terms of cultural significance, you should research the presence of known or suspected ceremonial areas, burial grounds, or archeological sites. Inventories of historic sites or landmarks, even though they include those on tribal lands, may not provide a full picture of the cultural and historic significance of your development site. Tribal Historic Preservation Officers or Cultural Resource Departments, for tribes with this position, can serve as a resource to gather this information; assist with interpretation; and make connections to tribal elders or other tribal members. You can also consult with tribes directly about the cultural and historic significance of your proposed site or its surroundings.

Reference resources:

-

For direct consultation on cultural and historic issues, look up contacts for Tribal Leaders here

-

This resource includes some tips on direct consultation on cultural and historic issues (even if you are not subject to Section 106).

-

The Environmental Protection Agency provides a recommended format for preliminary environmental reports and links to USDA’s electronic PER format

-

Indian Land Tenure Foundation outlines types of easements for rights-of-way and process to obtain them in this procedural handbook

-

Open Energy outlines the right-of-way process on tribal land in this flowchart

Factor #2. Infrastructure capacity and needs

The creation or rehabilitation of new homes and adding or upgrading infrastructure go hand-in-hand.

Infrastructure plays a critical role in Native peoples’ ability to meet their everyday needs, but many tribal communities, particularly those in rural areas, lack basic sanitation, energy, and technological infrastructure (such as broadband Internet) as persistent and widespread infrastructure needs. Because these needs persist in many tribal communities, infrastructure is one of the largest costs associated with development on tribal land. On the other hand, without consistent infrastructure, residents pay high costs for basic services, such as electricity and Internet.

As you vet potential sites for your project, you should evaluate infrastructure needs, including existing connections to the site across different systems and the impact of your proposed development on existing water supplies and wastewater systems (in addition to others). You may want to engage an engineer to assist you with this evaluation through a preliminary engineering report (PER) to identify the major technical components of a site. A PER may be needed if you are seeking funding for infrastructure from federal agencies.

As you assess infrastructure, it will also be important for you to understand if any infrastructure improvements or extensions will require use of the right-of-way through an easement. Infrastructure that typically requires right of way easements are power, telecommunications/broadband, and transportation. Ideally, you should consider alternatives to an easement whenever possible to protect tribes’ property rights.

Consider the following components of utility and infrastructure access and reference any tribal land maps during the site selection process:

-

Presence: Does the site already have infrastructure and utility services?

-

Proximity: For sites without existing services, is the site near main lines to connect to infrastructure and utility services?

-

Capacity: Is there capacity for additional hookups to existing infrastructure or utility lines? For instance, even when water and sewer lines are present, capacity for additional hookups to existing lines may be limited. Some communities impose moratoria on infrastructure hookups to assist with water resource management. In older urban areas, infrastructure may need to be improved significantly due to age or to support higher-density development planned for the site. These costs are often passed on to developers.

-

Fees: What is the municipal fee structure? You may be required to connect to a municipality’s water and sanitary sewer system if the site is in its extraterritorial jurisdiction. This is more complicated on checkerboard reservation lands, where tribal trust lands may be mixed with fee simple or county land, and the easement process should account for this.

Infrastructure and utilities to assess include the following:

-

Water lines

-

Sewer lines

-

Trash service

-

Electric

-

Gas

-

Broadband

-

Transportation access (both frontage roads and road access)

WAYS TO LOWER INFRASTRUCTURE COSTS

You may be able to lower the costs of infrastructure improvements on your site by phasing your project, using different site configurations or features, or seeking out partnerships:

Phased development enables you to plan for and make significant infrastructure improvements to an entire site, even if your project may be built on a portion of the site. Over time, more homes can be built on the same site without similar improvements. You gain efficiencies in terms of outreach to key agencies and lower the long-term time and costs associated with studies and assistance to navigate different regulatory requirements for different funding sources.

Denser development can create efficiencies in the use of public infrastructure and services. Denser development saves 38 percent on the delivery of upfront infrastructure, and 10 percent on the cost of delivering public services. For the purposes of engaging tribal leaders on denser development, it’s important to note that denser development does not necessarily mean multifamily development; rather it could mean single-family homes in closer proximity to one another (~5 units per acre).

Green infrastructure or low impact design refers to infrastructure that mimics natural systems to provide the functions that gray infrastructure (pipes, wastewater treatment facilities) typically provides. It can be used to manage stormwater runoff, sewer overflows, mitigate natural hazards, and revitalize contaminated brownfield sites. Its benefits include preserving and promoting biodiversity, water and air quality, and resilience to climate change.

Partnerships with public agencies can help lower infrastructure costs through strategies such as cost-sharing and use of multiple financing sources. For example,the Office of Hawaiian Affairs partnered with the Department of Hawaiian Homelands (DHHL) to pay down the debt service on $90 million of DHHL bonds used for infrastructure costs.

Factor #3. Land use context & zoning

During site selection, it is important to understand the land use context that governs development on your site. Tribes have the authority to regulate land use and development on tribal lands, with the primary exception being fee simple land owned by tribal members. Yet, developers working on tribal lands may experience a wide range of land use contexts and regulations, including no regulations. For instance, some tribes have Tribal Planning Departments that undertake planning efforts, such as comprehensive planning, and adoption and administration of zoning codes that regulate land use, density, and other aspects of development on tribal lands, and require development approvals by a Planning Commission. Some tribes do not carry out planning or have standards to guide land use or development on tribal lands.

Tribes with zoning codes

For tribes with zoning codes, also known as building codes, you will need to assess the current zoning to understand if your site is zoned for the project you want to build on the site. You can assess current zoning by:

- Engaging tribal planning and zoning staff about your project

- Working with your tribe’s legal department or consulting with a land use lawyer about your project

- Reviewing the zoning code standards (for tribes with published zoning codes)

Your assessment should focus on your project’s overall compatibility with current zoning standards. Is your project a permitted use? If not, you will likely need special approval from the Tribal Planning Commission or another decision-making body for you to build on your identified site. Can your development be configured to meet all the zoning specifications (such as height, density, lot coverage, setbacks). If not, you will likely need a variance for some of these specifications.

Reference resources:

Tribes without zoning codes

Some tribes do not carry out planning or have standards to guide land use or development on tribal lands or vary in what is regulated. When a tribe does not have a zoning code to regulate uses and site features or a master plan to guide development decisions, you have an added responsibility to build consensus among tribal leaders and members about overarching goals and specifics of your project. Make sure to include ICC or equivalent inspections in your construction schedule, even if you do not have zoning codes or building codes.

Site alignment with Financial resources

From a strategic standpoint, you can use site selection to increase your competitiveness for housing financing by assessing sites relative to eligibility or scoring criteria used to award the LIHTC or access financing available through Government-Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs). This may also apply to state-level QAP funding.

Alignment with states’ Qualified Allocation Plans

When state housing finance agencies use a Qualified Allocation Plan (or QAP) to award tax credits to affordable housing developers, scoring criteria often focuses on locational factors, such as transit service to or near a site or proximity to destinations, like healthcare facilities or schools. In more rural parts of the country, emphasis on access to destinations and transit can be a disadvantage.

Nonetheless, understanding your site’s location relative to factors in your respective state’s QAP can help increase your competitiveness for LIHTC financing. Nine (9) percent tax credits provide a larger amount of equity for affordable development projects, but are awarded on a competitive basis, with the highest scoring projects receiving the subsidy.

Aligning your site selection with your state’s QAP locational factors can help increase your project’s overall competitiveness for this financing. Examine QAPs for the following priorities for tribal housing, which will provide more information about specific site factors to consider:

-

Tribal housing set-asides

-

Tribal housing preferences

-

Rural policy pools or set-asides

-

Permanent Supportive Housing set-asides or preferences

Additionally, you should consider direct outreach to staff at your state’s housing finance agency, both to shape overall scoring criteria and provide concrete examples of when sites on tribal lands don’t align with QAP scoring criteria. Specific examples of misalignment can help with more systemic changes, and in some states, communications with housing finance agencies about priority projects can result in awards where discretion exists.

Alignment with Duty to Serve markets

Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae’s Duty to serve program offers mortgage lending in three housing areas—manufactured housing; affordable housing preservation; and rural housing—in underserved markets. Their lending includes providing financing for small financial institutions and financing for small multifamily properties in rural areas would receive Duty to Serve credit. These markets include rural, Indian Areas; look up eligible Indian Areas under Duty to Serve here.

Gaining site control

After you have identified a site for your development through site selection, you will then need to gain “site control.” Site control in its broadest sense means “some form or right to acquire or lease the [development] site.”[62] On tribal land, housing development typically occurs through long-term leases, and by extension, site control means understanding the land tenure status in use and how to pursue the appropriate approvals to build on tribal land.

Understanding the leasehold process

Once you have identified the land tenure status of your site, you will move to the leasehold process. This process will vary depending on land tenure status and if the tribe has developed its own leasing regulations under the HEARTH Act. The Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe’s overview of its leasehold process outlines two different tracks for its leasehold process: one on tribal land and one on allotted land.

These tracks demonstrate the two main avenues for obtaining a lease on tribal land for development:

-

Direct leasing with federally recognized tribes – The federal HEARTH Act enables federally recognized tribes to develop their own leasing regulations and execute leases directly with developers. As a result, tribes have developed their own leasehold processes. In this process, you will work more closely with tribal leaders and their respective housing or development entities to obtain your Title Status Report. This option provides benefits when undertaking housing development, such as more certainty and shorter approval timeframes, which can aid in meeting financing or program deadlines. At the same time, individual tribal leasing regulations will vary, meaning that familiarity with one tribe’s leasing regulations may not translate to experiences working with other tribes.

-

Leasing through the Bureau of Indian Affairs – This avenue requires leases on tribal land be approved by the Secretary of the Interior. For practical purposes, this authority has been delegated to BIA Regional Directors or agency superintendents. In this process, you will work more closely with representatives from the Bureau of Indian Affairs through a more standardized process to obtain your Title Status Report.

Obtaining a Title Status Report

As the process from the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe shows, regardless of the track, your goal at the end of the leasehold process is a Title Status Report. Regional BIA offices maintain land title information and issue Title Status Reports (TSRs). These reports show information that could affect your development, such as rights of way, easements, or mineral rights, and lenders typically require title information prior to extending financing to a developer.

Gaining a Title Status Report can be time-consuming; one study estimated the median approval time for a Title Status Report from BIA was more than 1 year (as of 2005).[63] Allocate ample time in your development plan and build relationships with regional BIA staff to help ensure your development is not stalled due to delays in receiving your Title Status Report.

[63] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2015). Obstacles, Solutions, and Self-Determination in Indian Housing Policy

[59] GAO-10-326 includes a list of commonly used programs for housing-related infrastructure in tribal communities (p. 46) + reports on types of infrastructure tribes have used IHBG to develop (p. 48).

[60] National Congress of American Indians. (2017). Tribal Infrastructure: Investing in Infrastructure in Indian Country for a Stronger America. An initial report by NCAI to the Administration and Congress. Available at: https://www.ncai.org/attachments/PolicyPaper_RslnCGsUDiatRYTpPXKwThNYoACnjDoBOrdDlBSRcheKxwJZDCx_NCAI-InfrastructureReport-FINAL.pdf.

[61] Report on Broadband Deployment in Indian Country, Pursuant to the Repack Airwaves Yielding Better Access for Users of Modern Services Act of 2018. Available at: https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-357269A1.pdf

[62] Corporation for Supportive Housing. (n.d.). “Establishing Site Control.” Available at https://www.csh.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/SiteControl_F.pdf.

Design

Once you have a site selected, it will be time to work with your architect, engineers, landscape architect, green building consultant, and other design professionals to create a development vision. The architectural plans and drawings will be necessary components of most development review processes and will create a specific plan for contractors to estimate costs and implement.

Developing the Site Plan

Developing the site plan will be the first step in the design phase of your project. A site plan should be developed by your design partner, who for all LIHTC projects must either be a licensed engineer or architect. Site planning is critically important to the lifecycle of your development and should include perspectives of all partners. An experienced engineer or architect will know what to include in the site plan, but a few high-level items include:

-

Land boundaries and dimensions

-

Streets, alleys, or roads adjacent or within property boundaries

-

Utilities serving the property or distance to point of connection

-

This one is especially important on Native lands where lack of such infrastructure can be a barrier

-

Building specifics (dimensions, designations, locations, etc.)

-

Retaining and garden walls and other accessory structures

-

Existing trees and other natural features [64]

Simply put, a site plan shows what already exists on the property, what you are planning to build on the property, and the relationship between the two. Required by local governments, site plan specifics will vary from place to place.

Thoughtful site planning will consider infrastructure, density, habitat protection, affordability, and access on Native lands as key elements of the process. It is also at the site planning stage that partners should begin to think about how to incorporate cultural heritage and community needs into site design. The Community Needs Assessment completed in the Visioning phase of the process should act as your jumping off point and inform the site plan development process.

Designing with your Tribal Community in Mind

Housing can and should be specific to each culture, place, and climate. A culturally-based design requires strong community engagement, which includes a variety of stakeholders, such as elders and tribal leaders. Thoughtful site planning and design can both sustain cultural heritage and natural habitat, two considerations important to Native communities.

Some Design Considerations:

-

Are there cultural traditions that could help the designer orient the site?

-

For example, should the opening face east, so residents can greet the sun each morning?

-

Are there traditional structures such as a longhouse or wigwam that might be reinterpreted in the design?

-

Are there local materials that could be harvested sustainably and incorporated?

-

Could health and wellness needs be addressed through a system of trails that bridge housing, nature and community access?

-

Could Tribal artists be commissioned to incorporate their work on site?

As you are working on your design, keep in mind that one size does not fit all. None of these questions may resonate with your community. Choose an architect carefully for their understanding of these matters and work with your designer and your community to identify what is most important and can honor the cultural traditions of your tribe as well as meet their housing needs. The Best Practices in Tribal Housing report published by HUD in 2013, has many examples of Native projects that took extra care to design with their community in mind.

Green building, sustainability, and health

What approaches and technologies will you incorporate into your development that will increase the energy and water efficiency, reduce the operating costs, create healthy conditions for your residents, and reduce your development’s environmental impacts?

There have been emerging approaches to construction in tribal areas that seize the technological changes in the construction landscape and foster more significant community stewardship. The EPA has developed a tribal green building toolkit that helps tribes maintain usage of the natural resources that have historically sustained them and make buildings healthier and more affordable.[65] This toolkit's primary use is for tribal government officials but can provide those in the development community insight on tribal green building priorities and evaluate different options to reach sustainability objectives. When reviewing this toolkit, it would be beneficial to review with your development team and identify what community priority areas should be included in the construction process.

Community priority areas include:

-

Public Health and Safety

-

Environmental Quality

-

Economic, Affordability & Financial Sustainability

-

Tribal Sovereignty & Self-Sufficiency

-

Tribal Culture & Community Development

Disaster resilience

Developments should be constructed or adapted for resilience against natural disasters, such as high winds, tornadoes, landslides, floods, winter storms, and wildfires. Specifics will vary by location and site, so ensure you understand your development’s susceptibility and work with your design team to mitigate risks. The Resilience Analysis and Planning Tool is one place to start.

Designing for people of all abilities

When designing your building, consider the implications for people with diverse abilities. There are multiple frameworks that may be useful to consider:

-

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) provides requirements and guidelines which you will need to follow when relevant. Your architect and design team can help you understand the implications for your development.

-

Visitability is a framework relevant for single family homes that focuses on making homes accessible and easy to navigate for residents and visitors who have trouble with steps or use wheelchairs or walkers. Some municipalities have adopted ordinances that require or encourage visitability in new homes. There are three basic requirements for a visitable home: at least one entrance with no steps, doors with 32 inches of horizontal clearance, and one wheelchair-accessible bathroom on the main floor.

-

Universal Design focuses on creating environments that “can be accessed, understood, and used to the greatest extent possible by all people regardless of their age, size, ability, or disability.”[66] This has implications for both designing the building itself and fixtures, features, and appliances within the building.

-

Trauma Informed Design: Trauma-informed design underscores that housing should not just put a roof over people’s heads, but should create dignity, healing, and joy. This impacts the design process and prioritizes the voices of future staff and potential residents to hear what they need in housing to feel safe, and for their voice to help lead the design – ensuring the housing meets the needs and honors the identities of the residents.

Obtaining Approvals

Approval processes will vary substantiality from project to project and among differing communities. Some jurisdictions have clearly defined and predictable approval processes where others are more complicated and require more work. The type of project will also impact the approval process. A redevelopment of an existing housing development will require far less review than new construction on a vacant site.

Working in tribal communities creates another layer of approvals and consideration, but in general the process is not any more or less complicated than for development outside of tribal boundaries. The chart below highlights a few high-level approvals and partners that you will need to work with throughout the process. Engaging these entities early on will help you get a better sense of the process and what the timeline will actually look like.

|

Approval Needed |

Description |

|

Partners |

Though not a mandated approval, it is critically important that all partners approve of the site plan and all other design elements. This will ensure fewer changes down the line and lead to a smoother design process. |

|

Tribal leadership |

This will vary based on tribe, but generally you should plan to have key tribal leadership groups approve all design documents and applicants for contractors. They should also be involved in all group conversations about design, in order to facilitate a smooth design process. |

|

Local regulatory agencies |

In addition to tribal leadership, ensure that you have all required approvals and buy-in from tribal and local regulatory agencies. This will vary among tribes, but a good place to start is with the tribal planning department. These might include Tribal Historic Preservation Office (THPO), Tribal Employment Rights Office, or a tribal reality office. |

|

State agencies |

If your tribe is partnering with your state or accessing state funds, such as a tribal set-aside, work with the agency to determine their approval process and build this into your process. Working with your local State Representative and or House Senate seat as well as the state housing finance agency are suggested as well. |

|

Leasehold |

There will always have to be some kind of leasing process, but it will vary depending on how the deal is structured. The complicated structure of tribal land makes the process different than in other developments but should be relatively easy to iron out in working with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, tribal leadership and the local planning department. |

|

Environmental Impact |

Every development will have to undergo an Environmental review. Work with the agencies outlined above as well as the Tribes EPA office to determine what this process will look like for your development. |

|

Land use (zoning review) |

This review confirms that your development plan is in line with local land use regulations. Typically, jurisdictions will issue a permit to confirm approval. This will be tied into your site selection phase covered in Phase 3. |

|

Site Plan & Engineering |

You will need formal approval of the site plan discussed in the section above. An approval will ensure that it complies with TERO ordinances along with local development regulations. Rehabilitation projects may require updating key systems and structures to comply with building code. |

|

Design |

Design and aesthetics approvals will confirm that the architecture and landscaping plan meet community needs outlined in the Community Needs Assessment. |

|

Building plans, permits, and inspections |

Once you have received approvals for all of the above, the developer can submit construction drawings to the building department to ensure that it is consistent with the site plan and complies with local building codes. Upon approval, building permits are issued and construction can begin. |

The process of obtaining approvals should be an opportunity for the tribe to formally exercise its power to shape development. In fact, community support can often be the deciding factor in getting the approvals you need to proceed with development. Community buy-in allows you to showcase the importance of your development and how it can best address local priorities, therefore increasing the likelihood of getting formal approval from the entities outlined above.

If you are a developer and not a tribal entity, keep in mind that tribal leadership can provide helpful guidance on design for cultural preservation and help guide you through the often-complicated land ownership structure on many reservations. Establish a relationship with these agencies early on in the process to facilitate smooth approvals.

Environmental reviews

Most projects are subject to some form of federal or tribal environmental reviews as the approval process to build your project. In general, projects entirely or partly financed, assisted, conducted or approved by federal agencies must comply with the National Environmental Protection Act (or NEPA), Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act, and Endangered Species Act. The overarching goal of these reviews are to prevent or mitigate adverse environmental impacts before development occurs.

For many tribes, understanding these impacts is embedded into their way of life and worldview. The Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe explains their environmental review process as “forethought and effort” to ensure “[land and resources] remain as whole, intact, and healthy as it was received so that it may sustain them.” These reviews have practical benefits for your development: environmental assessments can uncover important site conditions to account for upfront, rather than as construction occurs.

For projects on trust land using federal funding from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the environmental review process typically follows HUD’s Part 58 process. Under this process, tribes (although not THDEs) can serve as “responsible entities” for the environmental review process. As a responsible entity, tribes have the authority and responsibility for the environmental review and decisions related to it. As a result, you may work directly with representatives from tribes to complete the environmental review process. Additionally, tribes may incorporate additional environmental reviews into their leasing regulations, so it is important to consult with tribes’ directly on their requirements.

If your project includes building new infrastructure, be prepared for a higher level of environmental review than if your project is being built on land that already has infrastructure. Projects that require infrastructure to be added or upgraded on the site require cross-agency environmental review, but these reviews follow the same process (whereas reviews of housing development vary more).

Based on tribes’ experiences, compliance with NEPA on tribal lands is more difficult than in other areas. A survey of tribes and THDEs to understand opportunities for better federal agency coordination found that “certain environmental concerns, such as the presence of endangered species or wetlands, are more likely to be a concern in rural areas, meaning that tribes are more likely to have to engage in consultation or mitigation to resolve potential issues” and “these areas are less likely to have digital maps or records available, which make data gathering more difficult.”[67] One way to streamline this process is to incorporate a reference to a NEPA document previously prepared by the agency overseeing the process or by another agency.[68] Per the HEARTH Act, where the federal government has undertaken an environmental review process in connection with a federally funded activity, the tribe can rely on that federal environmental review.

Cultural or historic reviews

Projects entirely or partly financed, assisted, conducted, or approved by federal agencies must comply with the National Historic Preservation Act. The overarching goal of historic and cultural reviews is to protect tribes’ sacred sites, historic landmarks, and cultural resources and landscapes. Many tribes have registered historic places, landmarks, and traditional cultural property on the National Register of Historic Places. At the same time, many tribes’ historic or cultural resources and landscapes may not appear on federal historic inventories, like the National Register of Historic Places, and markers of their cultural and historic heritage are under threat.

Projects with support or seeking approvals from federal agencies will be subject to the National Historic Preservation Act’s Section 106 consultation process. This process requires the agency to seek, discuss, and consider the views of stakeholders, including State or Tribal Historic Preservation Officers (SHPOs/THPOs) and members of Federally recognized Indian tribes.

Site visits and interviews with tribal elders and cultural experts may be some of the best sources to understand the historic and cultural landmarks and places in and around your site. Keep in mind that some tribes may not want to share the existence of location of properties of cultural significance, due to their belief systems, and Section 106 has workarounds to account for the desire for this confidentiality.

Reference resources

-

More examples and case studies in Best Practices in Tribal Housing (2013)

-

Search for Tribal Preservation Programs through this site from the National Park Service.

-

Consultation with Indian Tribes in the Section 106 Review Process: A Handbook by the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation

-

The Bureau of Indian Affairs, Division of Natural Resources catalogs a series of resources related to BIA NEPA requirements.

-

Council on Environmental Quality and Advisory Council on Historic Preservation by NEPA and NHPA: A Handbook for Integrating NEPA and Section 106

Building Codes on Trust Lands

Building codes are generally understood to be unquestionable safety measures that are designed to prevent disasters. Every new code is a response to a disaster and as society moves forward, building codes will continue to evolve to protect all of us who spend time indoors. Building codes are not always a part of traditional tribal governments and even when they do exist, they are often only lightly enforced.

There are documented instances of poor housing construction leading to health effects such as asthma and other respiratory illnesses.[69] There have also been instances where poor housing construction has led to building collapses that put the lives of residents in danger.[70]

When building codes are not enforced, or non-existent, off-reservation contractors do not have anyone to answer to when it comes to the quality of work they leave Tribal communities with. This picture is a dialysis clinic after a tornado ripped half the roof off, burdening patients with travel to another clinic many more miles away. After inspection of the roof, it had been found that the contractor used nails instead of screws where the damage occurred. This demonstrates the importance of following best practices and enforcing building codes.

Construction professionals are often heavily guided by building codes and building code enforcement. However, when the codes are ambiguous or only occasionally enforced, it can be difficult to regulate. For this reason, we cannot emphasize enough the importance of selecting a Native construction partner that has extensive experience in construction projects in Native communities and that is up to date on building codes and materials. If a Native construction partner is not available to you, the second-best option is a partner that has experience working in Native communities in the past.

In addition to working with a trusted construction partner, it is important to set expectations and guidelines for your contractor. They should be written into the contract where possible. Part of this should include the expectation that mandated inspections are included at the end of every phase of construction. If a tribe doesn’t have building codes in place, you can use nearby local government building codes to help guide your process. Also make sure to consult your Tribal housing authority and Tribal Employment Rights Office/Ordinance (TERO). They are familiar with the building inspection process and can be guiding partners throughout the process.

Climate Resilience and Sustainable Development

It is critically important to consider climate resilient building practices when in the design phase of development. Ensure that you have a design consultant or architect that is familiar with climate-smart building practices, also known as Green Building, and that can advise you on how to implement strategies to mitigate potential impacts of climate change. There are a number of features that you can consider that mitigate the impacts of climate change, including, but not limited to:

-

Efficient use of energy, water, and other resources

-

Use of renewable energy, such as solar energy

-

Pollution and waste reduction measures, and the enabling of re-use and recycling

-

Good indoor environmental air quality

-

Use of materials that are non-toxic, ethical, renewable, and sustainable

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has developed a suite of Green Building Tools for Tribes that includes a toolkit, case studies, funding sources, and more. Check it out here:

-

Consideration of the environment in design, construction, and operation

-

Consideration of the quality of life of occupants in design, construction, and operation

-

A design that enables adaptation to a changing environment

When selecting a design partner for your process, make sure that they have experience with designing buildings that include the climate resilient and green building elements that are a priority for your community.

[65] https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2020-05/documents/tribal-green-building-toolkit-mobile-2015-rev2.pdf

[66] Centre for Excellence in Universal Design. “What is Universal Design.” Accessed: August 1, 2021. http://universaldesign.ie/What-is-Universal-Design/

[67]Coordinated Environmental Review Process. (2015). Report prepared by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Available at: www.hud.gov/sites/documents/COORENVIRREVIEW.PDF.

[68] Coordinated Environmental Review Process. (2015). Report prepared by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Available at: www.hud.gov/sites/documents/COORENVIRREVIEW.PDF.

[69] Nate Seltenrich. Healthier Tribal Housing: Combining the Best of Old and New. Environmental Health Perspectives. Retrieved from http://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/120-a460/. Accessed October 12, 2021.

Using elements of green design, the Santo Domingo Tribal Housing Authority was able to access tax credits to develop their next project. These 41 units of affordable rental housing were a result of a 2015 Low Income Housing Tax Credit allocation to the tribe. Leveraged against an Indian Housing Block Grant, the project has also worked to incorporate creative placemaking and connecting residents to better health and quality of life.

The property provides access to traditional healthy lifestyles through the heritage trail nearby and a community garden for food sovereignty, as well as modern health screenings. Outside the housing project, further community building has been spurred through several public art displays along the heritage trail, engaging with tribal artisans in the process.

At Santo Domingo, the desert climate and high heat made green design not only an environmentally-conscious choice, but also an economic one. The design reduced water usage, a critical resource in the southwest and for the tribe. Additionally, lower utility bills as a result of the green building design benefit low-income residents. For others interested in green design, urge lenders and residents to be patient with the longer timeline and acknowledge that cost savings come later.