Phase 3: Securing Funding

Now we get to the section that most developers want to know about: how do I get money for my project? Before you read ahead, know that previous steps in this process, like conducting a market study and developing a project budget, are critical because they are required by certain funders.

Developing multifamily housing can take years, and it's no different on Native lands. You might have to apply to the same funding source for multiple rounds before being awarded or start a conversation with an investor before realizing your project isn’t a good fit. Do not give up! Your patience and persistence will pay off.

This phase includes potential funding sources to get started with, and advice along the way. Including:

-

Understanding Public Sector Funding Sources

-

NAHASDA

-

LIHTC

-

Accessing Private Sector Funding

-

Working with Lenders

-

Working with Investors

-

Layering Financing

Understanding Public sector Funding Sources

Securing financing is a critical piece of the development process and once you have a more complete picture of your financial feasibility, you can begin to explore sources of financing available. There are a number of public sector financing sources to develop land and construct housing available to tribes, TDHEs, and other developers. Financing depends on a range of factors including capital needs, size, and location, to name a few. Often for federal grants you may have to apply in one year, wait until the next year to receive the funding, or if you are not awarded, wait until the following year’s cycle to apply again. A list of the most common sources of funding for housing development on tribal lands can be found below.

|

Funding Source |

Description |

|

Indian Community Development Block Grant (ICDBG) Funds |

Tribes and TDHEs are eligible for ICDBG funds, which may be used for housing development. |

|

Title VI |

HUD provides Title VI loans for development to tribes and TDHEs. The purpose of the Title VI loan guarantee is to assist IHBG recipients (borrowers) who want to finance additional grant-eligible construction or development at today’s costs. Tribes can use a variety of funding sources in combination with Title VI financing, such as low-income housing tax credits. Title VI loans may also be used to pay development costs. |

|

Indian Housing Block Grant (IHBG) |

Established by NAHASDA, IHBG is the most dependable source of funds for housing on tribal lands and is typically the starting point for most development projects. One-third of tribal grantees receive less than $250,000 annually from HUD, and often money has to be combined over multiple years, among smaller tribes, or leveraged with other funds. |

|

Native Hawaiian Housing Block Grant (NHHBG) |

The use of NHHBG funds is limited to eligible affordable housing activities for low-income Native Hawaiians eligible to reside on Hawaiian home lands. The Hawaii State Department of Hawaiian Home Lands (DHHL) is the sole recipient of NHHBG funds. Development activities that are currently being implemented by DHHL include site improvements for new construction of affordable housing. |

|

Tribal Funds |

Tribes may elect to designate a portion of their funds for housing development costs. |

|

HUD Section 184 |

Tribes, individual tribal members, and TDHEs are eligible to borrow funds for development from approved HUD Section 184 lenders. Tribes must have mortgage codes in place to be eligible. |

|

New Market Tax Credits (NMTC) |

The NMTC Program incentivizes community development and economic growth through the use of tax credits that attract private investment to distressed communities. |

|

Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) |

LIHTC provides funding for the development costs of low-income housing by allowing an investor to take a federal tax credit equal to the cost incurred for development. LIHTC credit properties are often rental properties for very low-income families but may be structured as rent-to- own units. |

|

State Housing Finance Agency Funds |

State housing finance agencies may have funding available for housing development, including federal funds (such as HOME funds) or state housing trust funds. |

|

Capital Magnet Funds |

The Capital Magnet Fund is administered by the Treasury Department’s Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund and provides grants to CDFIs and qualified nonprofit housing organizations through a competition. The funds can be used to finance affordable housing activities, as well as related economic development activities and community service facilities. |

|

Home Investment Partnership Program (HOME) |

HOME was created by Title II of the National Affordable Housing Act of 1990 and is the largest Federal block grant to state and local housing for low-income households. The program is meant to expand the supply of affordable housing with a focus on rental housing for very low-and-low-income residents. HOME can be used for a variety of purposes including acquisitions, rehabilitation, new construction, tenant-based rental assistance as well administrative and planning costs of Community Housing Development Organizations (CHDOs). Funds are administered on the jurisdictional level so tribes and TDHEs should review state Consolidated Plans to learn about available programs. |

|

USDA Rural Development Program (RD) |

The Rural Development Program offers a number of programs that provide development financing, including Section 502 Housing Direct Loans (homeownership), Section 502/523 Mutual Self-Help Technical Assistance Housing Program (homeownership), Section 502 Guaranteed Loan Program (homeownership), Section 504 Home Repair Grant/Loan Program (homeownership), Section 533 Housing Preservation Grants (homeownership & rental), Section 515 Rural Rental Housing Loans (rental), and Section 538 Guarantee Program (rental). All of these programs fall under the Rural Housing Service wing of the RD program and are coordinated by the USDA Rural Development State Office. |

| HUD Continuum of Care (CoC) | The Continuum of Care (CoC) Program is designed to promote communitywide commitment to the goal of ending homelessness; provide funding for efforts by nonprofit providers, and State and local governments to quickly rehouse homeless individuals and families while minimizing the trauma and dislocation caused to homeless individuals. |

| Federal Home Loan Bank | By law, each FHL Bank must establish an Affordable Housing Program (AHP), and must contribute 10 percent of its earnings to its AHP. AHP funds finance the purchase, construction, or rehabilitation of owner-occupied housing for low- or moderate-income households, as well as the purchase, construction, or rehabilitation of rental housing where at least 20 percent of the units are affordable for and occupied by very low-income households. The AHP leverages other types of financing, and supports affordable housing for special needs and homeless families, among other groups. They have a competitive program and a homeownership set-aside. |

Additional resources that outline more extensive lists of potential funding sources include:

NAHASDA on Native Lands

Decades of underfunding and poorly executed housing programs for Native communities led Congress to enact the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act (NAHASDA) of 1996. NAHASDA combined multiple federal housing programs and created a single block grant for Indian tribes or Tribally Designated Housing Entities (TDHEs)--including Alaskan Villages–known as the Indian Housing Block Grant (IHBG). Today the legislation extends to Native Hawaiian homelands.

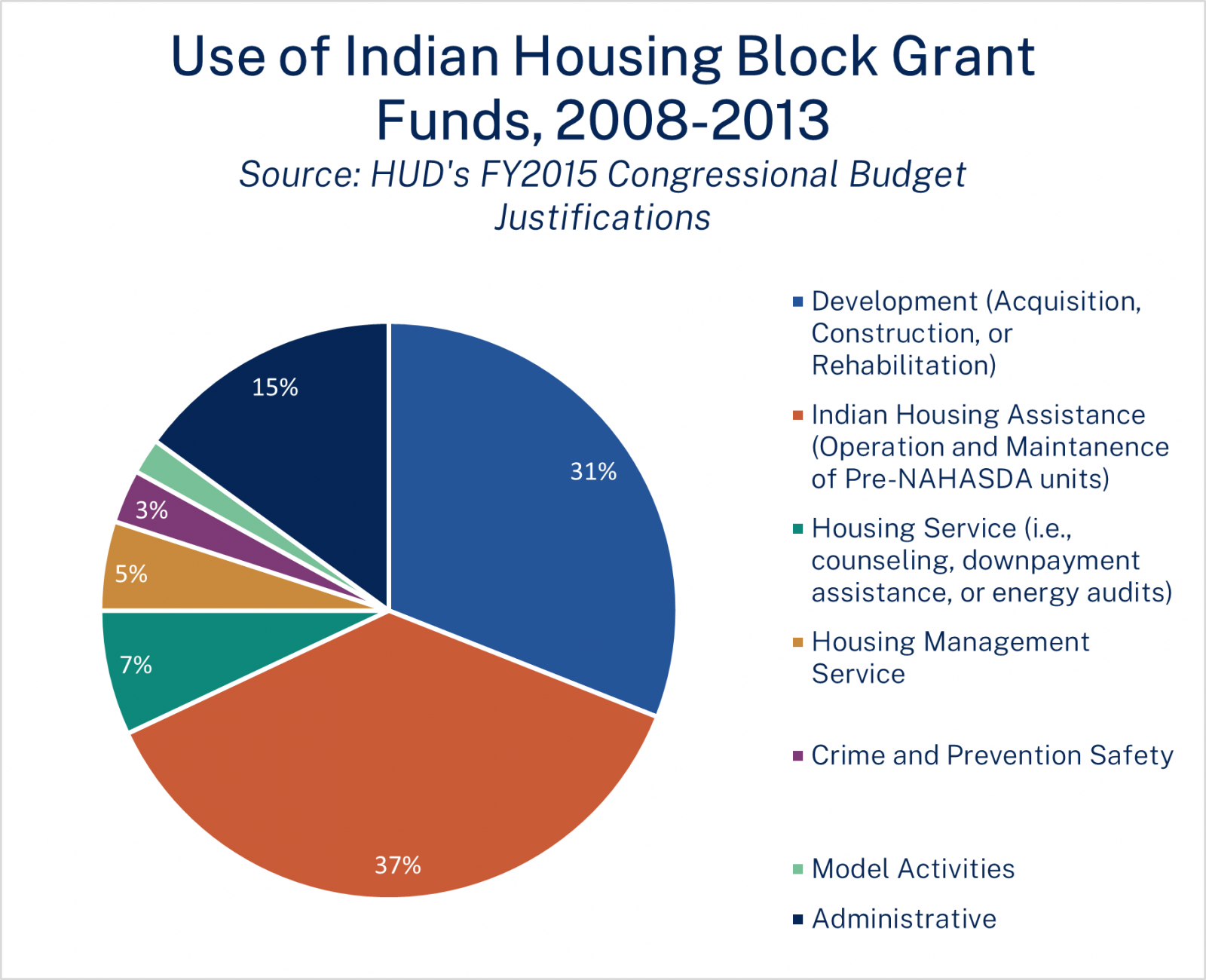

Although funding levels have remained too low to meet the needs outlined above, activities eligible to be funded with IHBG assistance include new construction, rehabilitation, acquisition, infrastructure, and various support services. Assisted housing under these funds can be either rental or homeowner units. Not only does NAHASDA give Native communities the ability to design housing programs better suited to members, but it also facilitates the leveraging of federal dollars with private funding, which is key to building more and better homes.

Competitive Formula

The Native American Housing Assistance and Self Determination Act (NAHASDA) is the law that guides the U.S. government’s approach in administering housing assistance to Native nations. NAHASDA is designed to support Tribal self-determination and give Tribes increased flexibility to allocate funding to their community’s development needs. NAHASDA consolidated previous HUD programs for Tribal development with a single program: the Indian Housing Block Grant (IHBG), which provides funding to Tribes annually. The amount of funds distributed to each Tribe through IHBG is determined based on a set formula that considers the size of the low-income population, current housing quality, and the number of households that are paying too much of their income on housing costs (i.e., households that are “cost-burdened”).[26] Tribes may also access additional IHBG funding on a competitive basis.[27]

Acknowledging the fact that NAHASDA funding is not nearly enough to even scratch the surface of Native American Communities housing needs, looking for opportunities such as the funding sources above to leverage with NAHASDA can increase housing production exponentially.

LIHTC On Tribal Lands

- Federal tax credits are allocated to state housing finance agencies by a formula based on population.

- Each state agency establishes its affordable housing priorities and developers compete for an award of tax credits based on how well their projects satisfy the state’s housing needs.

- Developers receiving an award use the tax credits to raise equity capital from investors in their developments.

- The tax credits are claimed over a 10-year period but the property must be maintained as affordable housing for a minimum of 30 years.

- Credits can be recaptured for noncompliance so maintaining close supervision over the properties throughout their lifecycle is important.

The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, commonly referred to as LIHTC, currently finances 90 percent of all affordable housing development,[28] with a growing trend for funding projects specifically on tribal lands. There have also been a number of IRS rulings that have led to the increased usage of IHBGs in conjunction with LIHTC credits. [29] The overall process for receiving LIHTC credits includes:

There are two versions of the LIHTC program, the competitive 9 percent program and the non-competitive 4 percent program. In some states, there is also a “state credit” (sometimes referred to as the “affordable housing tax credit”) which can be coupled with the 4% credit. The two programs allow investors to claim a credit equal to 9 percent or 4 percent, respectively, of their investment each year for ten years. Depending on market conditions, 9 percent credits could provide up to 70 percent or more of the equity needed for new construction or rehabilitation.[1] The majority of LIHTC projects in Indian Country have involved the competitive 9 percent program because of the larger share of equity it provides.

One of the main barriers to the development of LIHTC properties on tribal lands is that they are typically unable to support hard debt or debt that requires monthly or annual payments. Instead, they must rely on equity, soft subordinate debt such as loans with below-market interest rates or flexible repayment terms, or housing grants. The primary reason for this challenge is that household income in tribal areas is generally too low to charge rents that would support hard debt. For this reason, LIHTC can and should be paired with other financing sources such as:

-

NAHASDA

-

IHBG

-

Title VI guaranteed loan

-

Housing Trust Fund

-

RD Section 515 loans

-

RUS water/sewer grant/loans

-

FHLB AHP

-

HOME funds

-

Renewable energy investment tax credit

-

HUD Continuum of Care funds

LIHTC Success in California

Through sustained efforts by tribal housing agencies, Native American housing coalitions, rural affordable housing advocates, and state and federal housing agencies, California developed the Tribal Housing Pilot Program. The program was the first LIHTC set-aside in California and led to the first award to an Indian tribe in California since the program was established in the state over 35 years ago.

This success highlights how partnership and collaboration can breakdown longstanding barriers of isolation and inaccessibility that plague Native communities across the country.

The case study, Native Americans and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program: Lessons from the California tells the story of this success and can act as a guide for how tribes can begin to work towards building support for increased LIHTC set asides in their states.

Unlike other funding programs, under LIHTC, the tribe or TDHE does not need to repay the investor’s equity contribution like a loan. The investors are, instead, paid by the U.S. Treasury and tribes or TDHEs are entitled to earn as much as 15 percent of the eligible project basis as a developer fee. Because tribes and TDHEs are not usually profit motivated, developer fees are often contributed to the project or used to cover professional fees for consultants, accountants, lawyers, etc.

The LIHTC program is administered by states and through their Qualified Action Plans (QAPs), they can create additional incentives to further reach tribal lands. In states with larger tribal areas, QAPs will assign either an explicit priority or larger credits to projects that serve tribal lands. Arizona and California both explicitly assign funds for proposals from tribal areas, $2 million and $1 million, respectively. Whereas an application for a development on tribal land in North Dakota is eligible for up to 30 percent higher credits than other applications and in South Dakota points are added for tribal lands in the selection process. As it stands right now, there are five states that have explicit set-asides or preferences for tribal housing in their state LIHTC programs: California, Arizona, North Dakota, Minnesota, and South Dakota.

Despite its challenges, many tribes have found success in developing quality, affordable housing for residents using LIHTC. Through outreach and discussions with tribal housing authorities, syndicators, and consultants with experience using LIHTC in tribal lands, Freddie Mac identified three primary factors that, when combined, enable successful implementation of LIHTC on tribal lands:

-

Strong leadership

-

Management stability

-

LIHTC expertise

Strong leadership and management stability are critical to facilitating outside partnership and effectively navigating the LIHTC process. LIHTC properties often take many years so this stability can be difficult to achieve, but through consistent documentation of process and sustained internal capacity, tribes are able to bring LIHTC to fruition. In addition, though most tribes do not have LIHTC expertise in-house, there are a number of consultants with LIHTC experience in tribal lands that can not only provide the expertise needed, but also build internal capacity and knowledge for future projects.[31]

[29] http://naihc.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Indian-Housing-Development-Handbook-2020-Single-Page.pdf

[26] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2015). Obstacles, Solutions, and Self-Determination in Indian Housing Policy

[27] For more information on the Indian Housing Block Grant Competitive Grant Program, see: https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/public_indian_housing/ih/grants/ihbg_cgp

Accessing private sector funding

In addition to public financing sources, affordable housing projects also can leverage private sector funds.

Commercial financing comes from the private sector, usually banks. Commercial financing usually takes the form of hard debt. There are mission-driven commercial financing options, such as Impact Development Fund, Enterprise Community Loan Fund, Mercy Community Capital, Capital Magnet Fund, and CDFIs, which offer more flexible development financing than conventional loans in order to support more housing development in low-income and underserved areas.

Philanthropic funding is funding from foundations, usually consisting of grants or in-kind support.

Working with lenders

Lenders decide whether to invest in a project by assessing how likely it is that they will not get paid back on a loan. They consider this risk in two ways: the risk that the project will not generate enough revenue to pay them back (“project risk”) and the risk that you, the developer, will not pay them back if the project is not completed (“borrower risk”). The riskier they perceive the project and borrower to be, the less likely they are to lend the money and the more likely they are to offer you unfavorable loan terms.

So, when you are seeking for private financing, focus on reducing uncertainty and increasing confidence in you and your project. Here are some tips and tactics you can pursue:

Working with investors

-

Proactively build your relationship with lenders. Reach out before submitting an application for funds to ask questions, hear from them about their loan process and requirements, introduce yourself and establish a relationship. Participate in events to help build rapport – for instance, Indian Business Alliance meetings convene a wide range of stakeholders, including community development and lending institutions.[32] This gives you the opportunity to build a network of others that can support your development, access information and assistance that can improve your project, and establish your credibility as a partner.

-

Get support from other community leaders. Tribal leaders’ support for your project can help address lender concerns and make lenders more comfortable with the process on Tribal lands. Having a letter of support or bringing a community leader when you meet with lenders can help demonstrate their support for your project. This shows lenders that there is community support and that others are willing to help make your project succeed.

-

Educate lenders on how the development process looks in your community. For instance, leaseholds are not well understood by many lenders and investors, which can make these transactions seem riskier.[33] To combat this, you may need to clarify the process and demonstrate your comfort navigating it to make lenders more comfortable.

-

Provide a reasonable assessment of financial feasibility. Show how you will be able to make the project balance out financially (or “pencil out”) if you get access to this funding. Provide documentation for any assumptions you make and acknowledge where there are risks, so you can show that you are prepared to address them. Finally, summarize the analysis in a format familiar to the lender – generally, this means assembling or adapting your pro forma package using their templates or guidance. Lenders will review this package with two metrics in mind: the Loan to Value ratio (LTV) and the Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DCSR or DCR). Check if the lender has published maximum LTV or minimum DSCR thresholds and use your feasibility analysis to determine if you need to adjust your model to align more closely with these standards.

-

Secure a loan guarantee. If you have a loan guarantee, that means the lender is guaranteed to be paid back, in full or in part, even if the project does not generate enough income. These guarantees are often offered by the public sector (e.g., the federal government offers loan guarantees through Title VI and Section 184 to Tribal developments).

-

Identify alternative income streams to secure loans. Although land is the most typical loan collateral in real estate finance, tribes may have alternative income streams at their disposal that could be used as collateral when land is not an option (e.g., when developing on trust land). For instance, some tribes have used third-party healthcare reimbursements, gaming revenues, and NAHASDA monies, among other revenues.[34]Alternative income streams as collateral works for Native CDFIs, such as Indian Land Capital Corporation.

Unlike lenders, who expect to be paid back regardless of project performance, investors take on the risk that they may not get their money back when investing equity in a project. In exchange, they become partial owners of the property.

Native CDFIs

While a lender is looking for their debts to be covered (DSCR or LTV), investors are estimating their rate of return. And they will usually only invest when they believe they will see some positive return on their investment. They get this return from revenues generated by the project (i.e., rental income or capital gains from selling the property). In some cases, investors may also receive tax benefits from the property. If a project doesn’t generate revenue, they don’t get paid back.

Many of the same tips for building relationships with lenders also apply to building relationships with investors, including proactive outreach and networking, cultivating support from community champions, and clear financial analysis.

[32] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (2012). Growing Economies in Indian Country: Taking Stock of Progress and Partnerships. Available at: https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/conferences/GEIC-white-paper-20120501.pdf

[33] Whaley, Kenneth. (2019). Low Income Housing Tax Credits and Affordable Rentals in Indian Country. The Center for Indian Country Development.

[34] Native Nations Institute. 2016. Access to Capital and Credit in Native Communities, digital version. Tucson, AZ: Native Nations Institute. Available at: http://nni.arizona.edu/application/files/6315/2822/4505/Accessing_Capital_and_Credit_in_Native_Communities.pdf

Layering financing

There is not enough public funding to fully address housing shortages, so it is important to leverage federal dollars with other sources. This is sometimes called “layering financing” or “leveraging financing.” For some tribes, annual allocations of federal funding will not be enough to finance a single development and it may require multiple years of grant allocations to assemble sufficient financing if other sources aren’t used. Leveraging or layering makes it possible for these dollars to go farther. For instance, the Cook Inlet Tribe was able to nearly triple the amount of housing built annually by taking advantage of NAHASDA and leveraging it with other funds.[35] However, leveraging is a relatively new concept to many tribes since public programs did not heavily encourage this approach before NAHASDA.[36]

Refer to the table of public sector funds for some of the programs commonly paired with NAHASDA. This is not an exhaustive list. Regional HUD offices can also help identify leveraging opportunities, but they do not provide assistance with completing applications for funding.[37] For further assistance with layering financing, you may wish to hire a consultant with experience in housing development on tribal lands or you can apply for technical assistance. All tribes that receive IHBG funding are eligible for no-cost technical assistance, which you can request through your local HUD Office of Native American Programs.[38]

Finally, always refer back to your pro-forma and development budget as funding is secured. Keeping these resources up to date will help you approach subsequent funders and demonstrate expertise.

Adapting programs to serve Native development goals

While many sources of public housing finance are available to Native communities, they were not all designed with Native communities in mind. As a result, you may need to be prepared that public program staff may resist or need assistance working with program regulations if the tribal context is new or unfamiliar.

Public funding applications imply a certain order of events in the development process. For instance, you need a detailed concept ready before you apply for most development funds. This can make it hard to spend significant time and resources on the design phase, limiting opportunities for creative or culturally appropriate design.[39] Having flexible pre-development resources can help account for this.

You may have to navigate duplicative requirements. For instance, you may be asked to complete multiple environmental reviews to satisfy the standards of different programs when layering sources. If you identify these overlapping tasks early enough, you may be able to create processes that satisfy multiple requirements at the same time and avoid duplicating effort. You may also need to clarify regulatory frameworks that do not align with tribal context (e.g., some funding sources set their own wage rules, but most tribes are permitted to pay either Davis-Bacon or their own wage rates).[40]

Statewide underwriting standards and financial assumptions may not align with tribal context. For instance, Tribes may adopt a maximum rent policy that sets rents lower than what is allowable by state and federal funding sources (and often these maximum rents are not determined based on a percentage of family incomes, unlike state and federal rent limits).[41] This means you may need to negotiate an exception or account for higher rents in your development project and find ways to offset them with rental assistance or other financial support for families with lower incomes.

Indigenous Design Trade-offs

In Phase I we talked about working with architects to create beautiful and community-informed structures. While there are numerous funding sources that can be used to cover the cost of designers and architects, including IHBG or any source for pre-development costs, there is always a tradeoff. The cost per square foot community space may end up being higher than a site plan with no community space, and lenders or funders will not see a guaranteed revenue for such spaces. Often, working with good design also means working with funders to understand higher costs of design if it’s done in a culturally informed way.

Overall, these difficulties reflect the limited engagement of Tribes in many state-level housing policy and planning discussions. That lack of engagement also limits how much funding flows from statewide housing programs to Native nations.[42] Additional engagement and advocacy between Tribal and state leaders can help create a friendlier environment for Tribal development by redesigning or streamlining processes with Tribes in mind and creating preferences or set asides for Tribal development projects.

Using Tribal Revenue for Housing

Making LIHTC work in Native Projects

Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTCs) can provide larger amounts of financing than typical allocations from other public finance programs, dramatically increasing the amount of housing construction possible in Tribal areas.[43] In this guide we focus on 9% tax credits.[44] Using LIHTC to expand and accelerate housing construction can also free up Tribes to use other, more flexible resources for different activities like infrastructure development, housing maintenance, or economic development. But making LIHTC work in Native communities requires persistence and creativity.

Common barriers to LIHTC in Tribal areas

Tips for success in building your LIHTC proposal

Despite the challenges, housing authorities and developers in tribal communities have found ways to make LIHTC work – as of 2018, Freddie Mac estimated that there were as many as 2,000 LIHTC properties, supporting over 80,000 units, in tribal areas.[56]

Capacity for an influx of funding

Having the capacity to administer funding is also an investment in your organization’s future, especially if you receive a large, unplanned influx of funding such as those authorized following a federal disaster through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) or appropriated through the American Rescue Plan.

The internal systems and controls that enable your organization to undertake a proposed development are the same ones that enable your organization to respond quickly to an influx of funding. Yet a significant amount of new funding can test the limits of your organization’s administrative capacity, especially when it comes with an urgency to meet a tribal community’s needs and administrative constraints, like tight timelines for use.

Here are three strategies to ramp up your organization’s capacity for an influx of new resources:

-

Staff up – As more funding becomes available, staffing may become a constraint. Depending on the role, opportunities may exist to draw on community-based networks or organizations already in close contact with tribal residents. For instance, can you hire local community members to assist with tenant outreach and marketing or train them to assist with eligibility screening processes? Can a local community-based organization play a more active role in your project’s visioning process?

-

Take a holistic view of available funding[57] – One way to use a large influx of funding is to direct complementary resources to support a wide range of individuals’ or communities’ intersecting needs. This approach stands in contrast to thinking first about the source of funding and its eligible activities. When you start by asking how funding can be used to meet community needs, you may find you are able to incorporate additional services into your project differently than if you focused on sources of funding. This aids with obligating and expending funding in a timely manner.

-

Plan for future opportunities – One challenge with a large influx of funding is being able to determine how to spend it in the funding’s timeframe. While this guide focuses on planning for a specific project, you can use new funds to undertake parts of planning and pre-development for future development opportunities. Additionally, you can assess more “shovel-ready” opportunities to support projects where you have already completed the initial development phases but lacked the resources to move forward.

Using housing first and harm reduction principles, these 10 units were developed to serve at-risk Native community members in southeastern Colorado. By going to tribal leadership first, pushing the state for more support, and using smart construction methods, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe now operates the first tribally-owned permanent supportive housing development in Colorado.

The project was first envisioned around 2015, after the first Permanent Supportive Housing Toolkit in Colorado was held. LeBeau Development LLC (now BeauxSimone Consulting), a national tribal supportive housing consulting company recognized the potential because they had a relationships with the Ute Mountain Ute tribe. The first step was to set up a meeting with the tribe's Chairman and walk through what supportive housing is, what the needs might be, and connect the tribal housing authority to other affordable housing resources in Denver. From there the project gained momentum by receiving a grant from Enterprise, connecting with other Section 4 grantees, and conducting a site visit to Duluth, Minnesota to visit the Gimaajii-Mino-Bimaadizimin, which is a transformational community that incorporate arts and culture into a PSH project. This site visit was instrumental to bringing the vision of the project together.

Working with the state of Colorado was a learning process. It started with a discussion about the historical context of the state of Colorado providing state funds for an affordable housing project for a tribe. Because the state of Colorado Division of Housing was so motivated to make this project happen, they engaged HUD to advocate to be able to use HUD Project Based Vouchers in the project, in order to provide a long term operating subsidy. Connections to the governor’s Commission of Indian Affairs played a key role in making this project successful. The state of Colorado agreed to fund the project with more than the typical per-unit amount. Monthly meetings on site with the different division directors kept the project moving forward, and included partners such as local health facilities and the police chief.

In a huge success for tribes everywhere, the project obtained an official memo from HUD that housing choice vouchers are eligible on tribal lands. Thanks to this decision, an often underutilized resource on tribal lands is now much more open, and other tribal groups outside of Colorado have been able to cite this memo to work with HUD vouchers in their state.

Finally, as sometimes happens with remote rural projects, the costs came in a lot higher than estimated, and initially the project was short $200,000. The Colorado Housing and Finance Authority was by this time quite invested in its success and provided gap funding.[35] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2015). Obstacles, Solutions, and Self-Determination in Indian Housing Policy

[36] U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2010). Tribes Generally View Block Grant Program as Effective, but Tracking of Infrastructure Plans and Investments Needs Improvement. GAO-10-326. Available at: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-10-326

[37] U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2010). Tribes Generally View Block Grant Program as Effective, but Tracking of Infrastructure Plans and Investments Needs Improvement. GAO-10-326. Available at: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-10-326

[38] More information is available here: http://naihc.net/technical-assistance/

[39] Enterprise Community Partners. (2020). Enhancing and Implementing Homeownership Programs in Native Communities. Available at: https://Nativehomeownership.enterprisecommunity.org/setting-stage-what-does-homeownership-mean-you

[40] California Coalition for Rural Housing & Rural Community Assistance Corporation. (2019). California Tribal Housing Needs and Opportunities. Availlabe at: https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/8d7a46_e7569ba74f5648ba9bc8d73931ebd85d.pdf

[41] California Coalition for Rural Housing & Rural Community Assistance Corporation. (2019). California Tribal Housing Needs and Opportunities. Availlabe at: https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/8d7a46_e7569ba74f5648ba9bc8d73931ebd85d.pdf

[42] Bandy, Dewey. (2014). Native Americans and the Low Income Housing Tax Credit Program: Lessons from the California Tribal Pilot Program. California Coalition for Rural Housing. Available at: https://www.frbsf.org/community-development/files/ci_vol26no2-Native-Americans-and-the-LIHTC-Program.pdf

[43] California Coalition for Rural Housing & Rural Community Assistance Corporation. (2019). California Tribal Housing Needs and Opportunities. Available at: https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/8d7a46_e7569ba74f5648ba9bc8d73931ebd85d.pdf

[44]Note: this section focuses on the 9% tax credit because it can be more difficult to access (since you need to compete for it) than the 4% credit and constitutes a larger subsidy, which is often needed for tribal housing developments to offset lower rents and a smaller scale of development.

[46] Bandy, Dewey. (2014). Native Americans and the Low Income Housing Tax Credit Program: Lessons from the California Tribal Pilot Program. California Coalition for Rural Housing. Available at: https://www.frbsf.org/community-development/files/ci_vol26no2-Native-Americans-and-the-LIHTC-Program.pdf

[45] Bandy, Dewey. (2014). Native Americans and the Low Income Housing Tax Credit Program: Lessons from the California Tribal Pilot Program. California Coalition for Rural Housing. Available at: https://www.frbsf.org/community-development/files/ci_vol26no2-Native-Americans-and-the-LIHTC-Program.pdf

[50] LIHTC in Indian Country. Freddie Mac. Available at: https://mf.freddiemac.com/docs/LIHTC_in_Indian_Areas.pdf

[47] LIHTC in Indian Country. Freddie Mac. Available at: https://mf.freddiemac.com/docs/LIHTC_in_Indian_Areas.pdf

[48] LIHTC in Indian Country. Freddie Mac. Available at: https://mf.freddiemac.com/docs/LIHTC_in_Indian_Areas.pdf

[49] Secondary market investors purchase loans from lenders. This makes lending more attractive to the lenders, since they can recapture loan capital and relend it to other borrowers. The major secondary market investors are Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae. In order to offer conventional mortgage loans that can be sold on the secondary market, these investors require the tribe to enter into a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU). This MOU outlines the ordinances, codes, and systems that need to be in place in order for the investors to purchase loans made in that tribal jurisdiction. For more information: Whaley, Kenneth. (2019). Low Income Housing Tax Credits and Affordable Rentals in Indian Country. The Center for Indian Country Development.

[53] For more information see the discussion of tenant selection and rental agreements in California Tribal Housing Needs and Opportunities (p. 58): https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/8d7a46_e7569ba74f5648ba9bc8d73931ebd85d.pdf

[54] California Coalition for Rural Housing & Rural Community Assistance Corporation. (2019). California Tribal Housing Needs and Opportunities. Availabe at: https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/8d7a46_e7569ba74f5648ba9bc8d73931ebd85d.pdf

[55] California Coalition for Rural Housing & Rural Community Assistance Corporation. (2019). California Tribal Housing Needs and Opportunities. Availabe at: https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/8d7a46_e7569ba74f5648ba9bc8d73931ebd85d.pdf

[56] Freddie Mac. (2018). Spotlight on Underserved Markets: LIHTC in Indian Areas. Available at: https://www.ncsha.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/LIHTC_in_Indian_Areas.pdf

[57] King-Viehland, Monique and Scally, Corraine Payton. “Five Ways State and Local Governments Can Strengthen Their Capacity to Meet Growing Rental Needs.” Housing Matters blog. Available at: https://housingmatters.urban.org/articles/five-ways-state-and-local-governments-can-strengthen-their-capacity-meet-growing-rental